-

Blog

The protection and democratization of undersea communications networks

Ensuring the security of the global, submarine communications infrastructure is becoming a priority for Western governments and agencies concerned that China and Russia are willing to use it for espionage, personal data theft, and general disruptive purposes.

Towards the end of 2023, the Defense Ministers of the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) – consisting of the United Kingdom, the five Nordic countries, the three Baltics, and the Netherlands – agreed to activate a JEF Response Action that would deploy multiple ships “as a military contribution to the protection of critical undersea infrastructure.”

Incidents of “hybrid’ or “gray zone” warfare – characterized by infrastructure sabotage, cyberattacks, and disinformation campaigns – are becoming more common as the world becomes increasingly reliant on the network of undersea optic cables that carry our data –from texts, emails, and social media communications to more sensitive information shared between governments and the military.

Russian and Chinese ships blamed for Finland-Estonia cable sabotage

The JEF response came after a string of incidents in which critical undersea infrastructure, in this case between the UK, the Baltics and Scandinavia, have been damaged. For example, in November, Finland and Estonia formally investigated damage caused to the Balticconnector gas supply pipeline and two significant telecom cables in the Baltic Sea.

While the investigation stopped short of providing evidence, two ships were known to have transited the region where the damage occurred and around the time it was discovered – a Russian nuclear-powered icebreaker (the Sevmorput) and a Chinese-owned container ship, NewNew Polar Bear. Photographs that appeared on X, formerly known as Twitter, on 24 October show the latter ship arriving in the Russian port of Arkhangelsk with its port side anchor damaged and several toppled starboard containers on its deck.

Investigating the same incident, Finland and Sweden found that the damage caused to the pipeline and both cables could only have occurred by a ship dragging its anchor for over 100 nautical miles – an incident that a ship’s captain would find difficult to ignore or to be unaware of. On 24 October, the Finnish National Bureau of Investigation announced that they had retrieved an anchor embedded in the seabed next to the damaged pipeline.

The importance of the incident cannot be underestimated as it exposes significant vulnerabilities regarding both energy and data security. The latest JEF response represents the tip of the iceberg when it comes to defending the world’s undersea communications network, which is quickly becoming a focus for Western governments.

The seen and unseen maps of global submarine networks

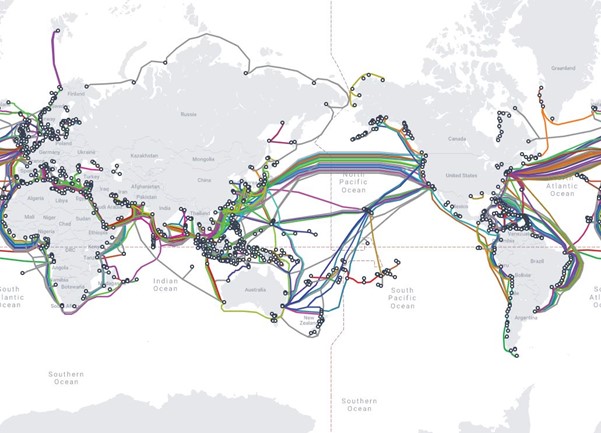

According to TeleGeography, there are an estimated 574 active and planned submarine cables (as of early 2024) covering around 1.4 million kilometers globally (see Figure 1). It also notes that accidents involving fishing vessels and ships dragging anchors account for two-thirds of all cable faults, making it difficult to not only monitor, but also to identify and prove deliberate damage.

Figure 1. Submarine telecoms cables, global map

Source: TeleGeography

In May 2023, for example, a group of Russian navy vessels entered the Republic of Ireland’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and remained there – thwarted only by Irish fishermen who refused to leave the waters. Ireland is an essential undersea cable hub, with multiple cables carrying data between the UK, Europe, and North America via southern Irish waters.

This begs several questions: “Who’s responsible for defending the undersea cable network?” In the case of Ireland, it is not a member of NATO, so would the United Nations be expected to step in should there be an attempt to sabotage the network? Also, “who is monitoring whom”, in terms of espionage, and “to whom does the data belong”?

Traditionally, undersea cables were owned by telecom carriers that would lease capacity to users. However, the expense of laying and maintaining the network has, in general, become too much for carriers, with money-laden technology companies and content providers, such as Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon, building private networks to carry the huge volumes of data now created by global users.

For example, Meta is building a 7,121km cable from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina to Santander in Spain, with completion set for 4Q24. The NEC-built cable is expected to offer 480 Tbps, which will eclipse the current record held by Google’s 340Tbps UK-US Grace Hopper cable.

Preferred and “high-risk” subsea cable manufacturers

Notably, while tech and content providers are bringing investment and investors to undersea cabling, there are only four companies in the world that manufacture and lay such cables – America’s SubCom, Japan’s NEC Corporation, France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks, and China’s HMN Tech (formerly Huawei Marine Networks). SubCom is known to be the US Government’s vendor of choice for sensitive projects.

US perception toward the threat of undersea communications sabotage and espionage was made clear in 2022 when Washington blocked HMN Tech’s involvement in building the See-Me-We 6 cable – a 19,000km line owned by a group of telecoms operators including India’s Bharti Airtel and Singapore’s SingTel that links Southeast Asia to Europe. Instead, the contract was awarded to SubCom, despite HMN’s bid being significantly lower.

In response, three Chinese carriers – China Telecom, China Unicom and China Mobile Limited – have invested $500 million in a cable network that connects China and France via Singapore, Pakistan and Egypt.

The move essentially places HMN Tech on the “high-risk” vendors list, much like Huawei’s exclusion from Western terrestrial 5G networks. In March, the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued a proposal that would require licensees to provide more information about who owns undersea cables. It also noted that any presence in US physical infrastructure by China Telecom is “highly relevant to the national-security and law-enforcement risks”.

De-risking subsea communications investments; Protecting private data

Legal intercept is a concept that allows governments to access personal data and communications of any individual for the purposes of criminal investigations and national security. However, there are no universal, global laws governing the process, meaning that governments can define their own laws.

Notably, countries such as China, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Russia have all explicitly expressed their ambitions to create a more centralized internet infrastructure, which could allow them to listen in to personal communications, and should they want to, to turn off specific websites or entire regions – a process that is not particularly technically challenging.

In this context, Western fears are well-founded – with observers concerned that we could be en route to a bifurcation of the internet, or more generally that malicious owners of undersea cables could use them to censor and spy on personal and business communications, and even exclude organizations or entire regions from international internet access.

It's clear that understanding who is building and who owns undersea cable networks, data privacy laws in different countries, and the identification of high-risk vendors (and their supply chains) is becoming a significant priority for Western organizations and governments.

Pamir has decades of experience of working with US enterprises, including multiple Fortune 500 companies, providing in-depth expertise and knowledge – including local intelligence – and actionable risk assessments. We can help with the necessary research and analysis to help you understand such complex issues – and, importantly, to de-risk your investments. Contact us today to find out who we can help.

China’s 5G influence in developing economies

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its digital counterpart, the Digital Silk Road, threaten to displace US telecom and tech companies in developing economies in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. How can US operators and network providers stand up to the challenge?