Pamir opinion: U.S.-China competition in building critical elements supply chains intensifies

Growing commercial and government concerns are intensifying U.S. efforts to diversify its critical minerals and rare earth elements supply chains as it’s far too reliant on imports, particularly from China.

According to JP Morgan, China produced 68% of the world’s rare earth minerals (used for making magnets and batteries), and 70% of graphite (used in lubricants, electric motors, and nuclear reactors) in 2022. China is also dominant in mineral processing, accounting for 100% of the world’s graphite supply, 90% of rare earths, and 74% of cobalt (also used in batteries) in 2022.

Critical minerals and elements are the backbone of U.S. technology and defense

Critical minerals are essential in the manufacturing of semiconductors, EVs, military weapons, batteries, and much more. But, according to the U.S. Geological Survey which has identified minerals and elements that are critical to the U.S. economy and national security, the U.S. was 100% reliant on imports for 12 of them – 5 of them from China.

The U.S. is 100% reliant on China for its Arsenic (used in semiconductors), Gallium (semiconductors and military applications), Graphite (lubricants, batteries, and fuel cells), Rubidium (electronics research and development), Tantalum (the manufacture of electronic components, capacitors, and superalloys), and Yttrium (used in the manufacturing of ceramics and lasers). The U.S. also relies on imports for 50% or more of its supply of an additional 29 minerals, including a 90% plus net import reliance for titanium, 14 rare earths, and bismuth.

On 3 July 2023, China set restrictions from 1 August 2023 requiring permission for exports of gallium and germanium (used in the manufacture of fiber optic cables), which was mainly aimed at the U.S. as part of the two nations tit-for-tat trade war. China has 94% of the world’s gallium resources and 83% of germanium – given their essential role in semiconductors, diodes, and fiber optics, it poses a particular problem for the U.S.

The concern is that China could choose to ‘weaponize’ its dominance of critical minerals, and use that to influence many other countries in southeast Asia that have also become reliant on its abundant mineral resources.

Rare earth elements, nickel, lithium, germanium and gallium are critical for defense systems, such as precision-guided munitions, nuclear applications, missiles, lasers, military communication, weapon systems, tanks, and radars. Meanwhile, copper, lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt, graphite, zinc, and rare earth elements are used in the manufacture of wind turbines, EV batteries, and solar photovoltaics, which are required for global decarbonization targets.

Meeting demand for critical minerals

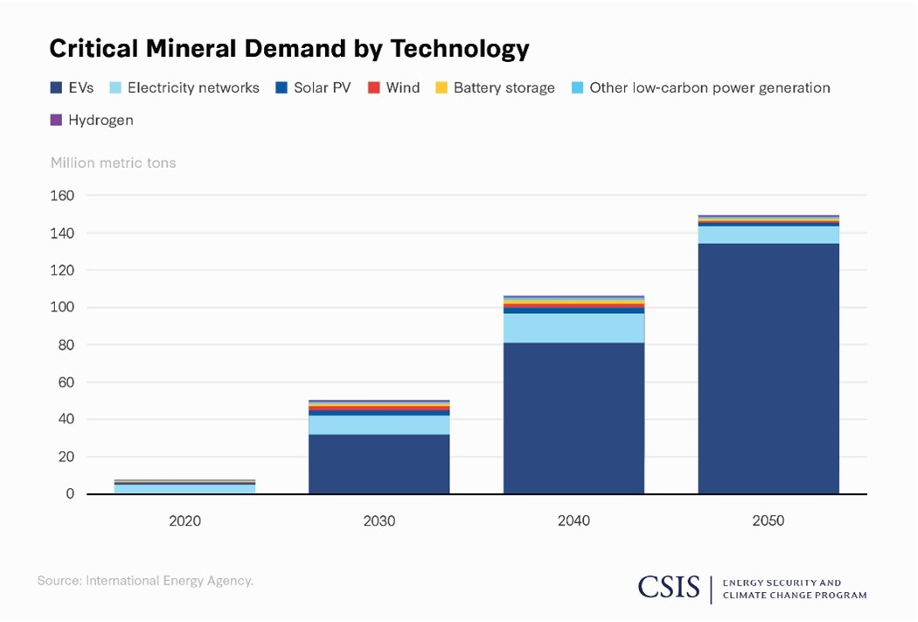

The graph below shows how much demand there will be for critical minerals by technology – a stark reminder of why the U.S. – which has few mineral resources of its own – needs to diversify its supply chains, rethink its reshoring foreign policy, and forge better relationships with nations other than China that have mineral and element resources. Central Asia, for example, has 38.6% of global manganese reserves, of 30.1% chromium, 20% of lead, 12.6% of zinc, and 8.7% of titanium reserves.

Figure 1. Critical mineral demand by technology

But unlike China, the U.S. has been late to the Central Asian opportunity. However, nations are often in debt to China and concerned about being dominated by Beijing, thereby making other partners an attractive proposition. The U.S. is held in relatively favorable regard and is trusted to fulfil its commitments by many nations in the region.

More recently, the U.S. has started to change its approach to the critical minerals supply chain by deepening partnerships with the Central Asian republics, such as Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. In February 2024, it also held the inaugural meeting of the C5+1 Critical Minerals Dialogue with Central Asian leaders, which is aimed at maintaining the security of critical minerals in the region and working towards market diversification.

A global effort to diversify critical element supply chains

Likewise, according to the IEA Critical Minerals Policy Tracker, there are over 200 policies and regulations that are attempting to reduce China’s dominance, including the European Union’s Critical Raw Materials (CRM) Act; the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act; Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy; and the US-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), a friend-shoring strategy involving 14 countries and the European Union to invest in and execute strategies to diversify critical minerals’ supply chains.

Also, on 18 June 2024, Congress announced the creation of the Critical Minerals Policy Working Group, a bipartisan working group to reduce China's dominance of critical mineral supply chains. The group "will work to create transparency into U.S. supply-chain dependency for critical minerals and develop a package of investments, regulatory reforms, and tax incentives to reduce that dependency."

But the U.S. could also learn some lessons from China itself, which has embarked on a decades-long trade-enabling infrastructure that plugs countries into a China-centric supply network for critical minerals. Going some way towards that, the U.S. has commenced similar trade strategies in Africa’s Lobito Corridor (Angola, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and in the Philippines Luzon Economic Corridor, which also includes Japan.

Concurrently, the Americas Act is aimed at building similar trade partnerships (and access to mineral and element resources) between the U.S. (via Florida, which exports 70% of the nations’ exports to Latin America) and the Americas as part of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement. Again, China already has influence in Latin America, so the U.S. has its work cut out.

In conclusion, the U.S. strategy to de-risk by reshoring faces steep challenges in the critical elements arena, due to its lack of domestic resources as well as a lack of skilled labor, which delayed the opening of TSMC’s semiconductor fabrication plant in Arizona. As a result, the U.S. needs to work on forging new partnerships with countries that have mineral reserves in much the same way that China has been doing for some years now.

China’s 5G influence in developing economies

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its digital counterpart, the Digital Silk Road, threaten to displace US telecom and tech companies in developing economies in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. How can US operators and network providers stand up to the challenge?