China’s dominance of the global supply chain for critical materials poses significant risk. How can Pamir help?

Advanced economies are looking for alternatives, as China holds much of the world’s reserves of critical materials and leads the world in the processing of these strategic materials.

At the turn of the year, China announced that it had found significant new reserves of copper in the Tibetan Plateau. As the world’s largest consumer of copper – which is used in electric motors, batteries, inverters, wiring, and electric vehicle (EV) charging stations – it will come as good news to China in the global struggle to secure and source critical materials. According to the International Copper Study Group, China accounted for more than half of the global copper demand and usage in 2023.

As of 2021, the Tibetan Plateau was estimated to have around 53 million metric tons of proven copper reserves. However, the latest discovery is estimated to add 20 million metric tons to the reserves, with researchers believing that there may still be up to 150 million metric tons of uncovered copper reserves in the region.

The region is considered to be China’s most important “strategic resource reserve base.” In addition to copper, it contains other important critical materials, including chromium, cobalt, lead, and zinc, together accounting for 30-90% of China’s reserves.

What is a critical material?

The discovery highlights the geopolitical importance of critical materials, which have many civilian and military applications. Those applications include EV batteries, magnets, green energy technologies such as solar panels and wind turbines, military equipment and weapons, and semiconductors and electronic components.

The U.S. Energy Act of 2020 defines a “critical material” as:

- Any non-fuel mineral, element, substance, or material that the Secretary of Energy determines: (i) has a high risk of supply chain disruption; and (ii) serves an essential function in one or more energy technologies, including technologies that produce, transmit, store, and conserve energy; or

- A critical mineral, as defined by the Secretary of the Interior.[1]

The Energy Act of 2020 further defines a “critical mineral” as:

- Any mineral, element, substance, or material designated as critical by the Secretary of the Interior, acting through the director of the U.S. Geological Survey.[2]

As of 2022, the U.S. Geological Survey listed 50 critical minerals.[3]

In addition, the U.S. Department of Energy has determined that the 17 rare earth elements (REEs), which are listed among the 50 critical minerals by the U.S. Geological Survey, “play a critical role to [U.S.] national security, energy independence, environmental future, and economic growth.”[4] The REEs are critical ingredients for multiple applications, including catalysts and magnets used in traditional and low-carbon technologies, such as magnets that drive wind turbines. They are also used in the production of special metal alloys, glass, and high-performance electronics.

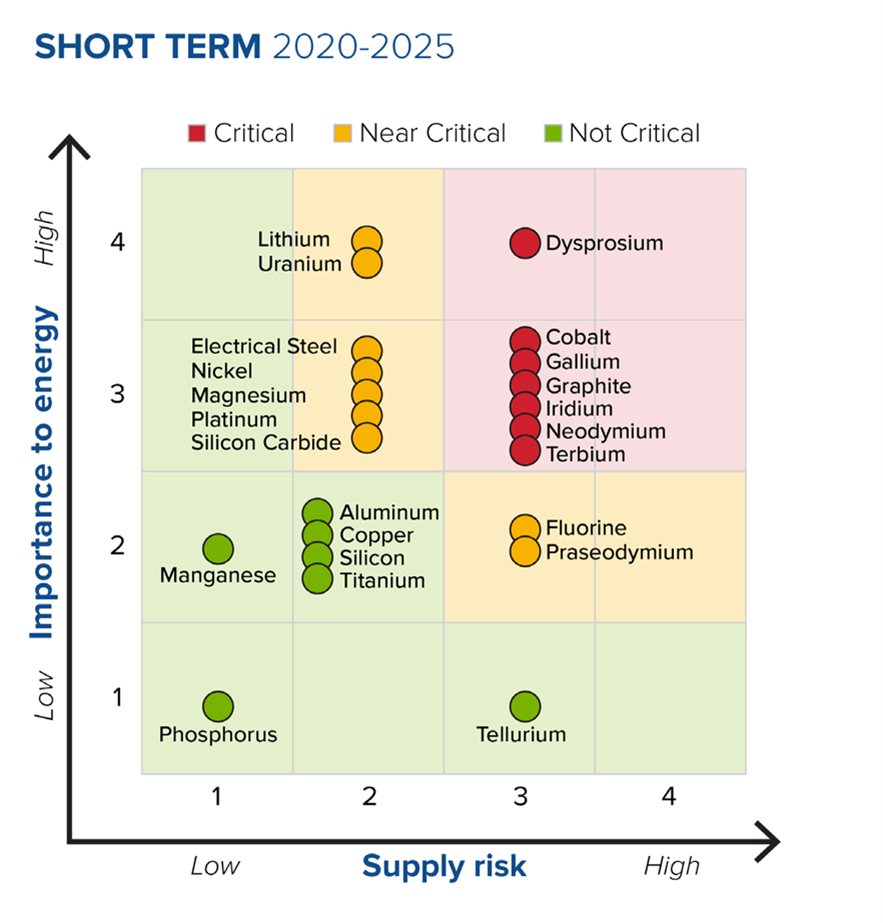

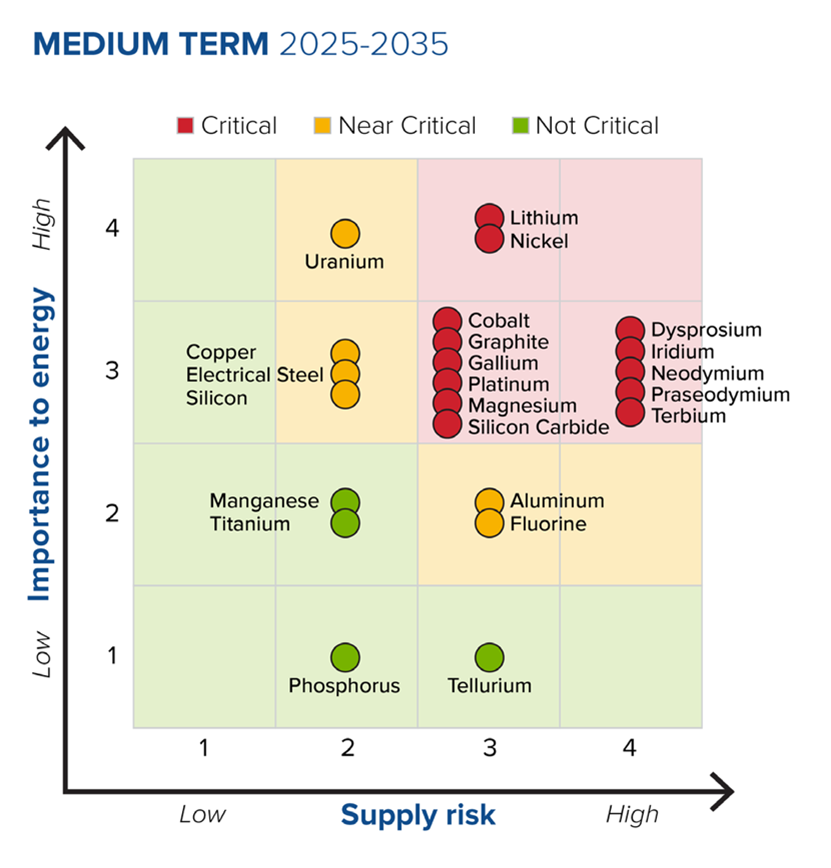

In 2023, the Department of Energy published its Critical Materials Assessment 2023, which highlighted those minerals considered to be “critical” or “near critical” – in terms of rarity and therefore a risk to global supplies – in the short- and medium-terms (see Figures 1 and 2 below).[5]

Figure 1. Short-term (2020–2025) criticality matrix

Figure 2. Medium-term (2020–2025) criticality matrix

Because these resources are often concentrated in specific regions around the world, they are considered to be “strategic,” as any disruption, notably geopolitical tensions, in the global supply chain would have significant impact on the world at large.

China’s dominance in critical materials processing

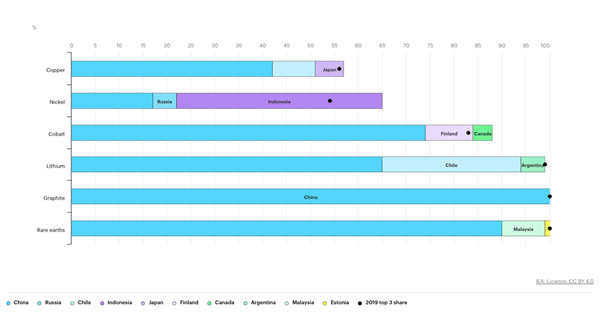

In addition to holding significant reserves, China has become the world leader in the processing of critical materials, thanks to the support of the Chinese government. According to the International Energy Agency, as of 2022 China was the world leader in the processing of copper (42% of the world’s total), cobalt (74%), lithium (65%), graphite (100%), and REEs (90%) – see Figure 3.[6] It was also the second-largest processor of nickel, after Indonesia, and accounted for 68% of global silicon processing.

Figure 3. Share of top three producing countries in processing of selected minerals, 2022

Source: IEA

Beijing has displayed a willingness to leverage its dominance to retaliate against what it perceives to be anti-China measures by foreign countries. In December 2024, it banned the export of gallium, germanium, and antimony to the U.S. Gallium and germanium are used in semiconductors. Germanium is used in fiber optic cables, and solar cells, among other things. Antimony is used in bullets and other armaments. China also placed stricter end-use reviews on the export of graphite to the U.S., which is an important component in EV batteries. Beijing’s export ban was announced after the U.S. government announced another round of export restrictions targeting Chinese semiconductor companies.

How can Pamir help?

In the face of Beijing’s willingness to exploit its dominance in the global critical materials supply chain to achieve its political goals, American companies must develop ways to mitigate risks associated with the evolving geopolitical landscape while advancing their business growth objectives. Pamir has experience and expertise in performing risk assessments – throughout the supply chain, including suppliers, partners, and people – for U.S. companies operating in China or partnering with Chinese entities. Our unique methodologies, local presence and knowledge, in-depth risk assessment, and comprehensive strategic advisory services can help you achieve regulatory compliance while minimizing business risks.

If you have any concerns, or questions, about sourcing materials from China, or working with local partners, Pamir can help.

We also help U.S. companies operating throughout the Asia-Pacific region, so contact us today to find out how we can help you minimize supply chain risk for strategic materials and discover new opportunities.

[1] https://www.energy.gov/cmm/what-are-critical-materials-and-critical-minerals

[2] https://www.energy.gov/cmm/what-are-critical-materials-and-critical-minerals

[3] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/02/24/2022-04027/2022-final-list-of-critical-minerals

[4] https://www.energy.gov/fecm/rare-earth-elements

[5] https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/doe-critical-material-assessment_07312023.pdf

[6] https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023/implications

China’s 5G influence in developing economies

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its digital counterpart, the Digital Silk Road, threaten to displace US telecom and tech companies in developing economies in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. How can US operators and network providers stand up to the challenge?